Did you know that today, May 19th, marks the 40th anniversary of Canada ratifying the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights?

In the spirit of international human rights commitments, CWP – along with the Social Rights Advocacy Centre and  the Charter Committee on Poverty Issues – presented to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights about the future of the newly-revitalized Court Challenges Program of Canada (CCPC).

the Charter Committee on Poverty Issues – presented to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights about the future of the newly-revitalized Court Challenges Program of Canada (CCPC).

Check out our presentation below or click here to listen to the audio (CWP’s presentation begins at 10:02 am):

Thank you for inviting Canada Without Poverty to appear at this important study on access to justice.

Canada Without Poverty

CWP is a federally incorporated, charitable organization dedicated to the elimination of poverty in Canada. Since our inception in 1971 as the National Anti-Poverty Organization (NAPO), we are governed by people with direct, lived experience of poverty, whether in childhood or as adults. This lived experience of poverty informs all aspects of our work.

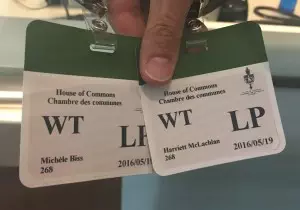

I am Harriett McLachlan, the President of CWP, and although I’m an educated professional, I lived most of my life in poverty. I have first-hand experience of the substantial barriers for access to justice for the 1 in 7 people in Canada who are living in poverty. I truly believe that if the justice system were accessible, I would not have endured 34 years of poverty. I am joined in my comments by CWP’s Legal Education and Outreach Coordinator and human rights lawyer, Michèle Biss.

The Barriers to Justice for People Living in Poverty

One of the principle barriers to accessing the justice system for people living in poverty is the lack of availability of financial resources. The cost of legal advice, administrative fees and other collateral costs directly restrict those living in poverty from accessing legal mechanisms.

In communities where legal aid is not available, primarily in civil and administrative matters, the most marginalized who are living in poverty are often denied justice. For example, as noted by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in their 2006 Concluding Observations, cuts in British Columbia for civil legal aid in family law services disproportionately affect women. Instead of remedying this service gap, B.C. took further measures to eliminate all funding for poverty law matters such as housing/eviction, welfare, disability pensions and debt.

We live in an era where social protections for the most vulnerable are under near constant threat. One of the underlying causes of the constant mining of such programs is attitudinal. In Canada, despite the obvious systemic nature of poverty, there remains a dominant discourse that stigmatizes poor people as undeserving and lazy. As a result, any provision of services, no matter how paltry, is deemed an act of benevolence on the part of governments, rather than governments meeting their human rights obligations to ensure the active participation in democracy of people who are poor.

The entrenched stigma associated with living in poverty is often internalized and can result in a fear of reprisal or further prejudice particularly when trying to claim their legal rights.

This fear of asserting one’s rights through the justice system is exacerbated by the growing trend of aggressive litigation by the government which asserts that the rights claims of this population should not be heard. For example, in the Tanudjaja v. AG case (also known as the right to housing case) when four homeless individuals attempted to assert their right to housing in the courts, the government respondent filed a motion labelling this exercise of rights as frivolous and vexatious. This left homeless people with no recourse to claim their basic human rights and occurred without any review of the 9,000 pages of expert evidence filed by the applicants.

The Court Challenges Program of Canada (CCPC) validates the legitimacy of poor people as rights holders – it acted as a mechanism to combat discriminatory stereotypes of poor people by providing access to justice.

The Court Challenges Program as a human rights mechanism

Prior to 2006 the Court Challenges Program was, in our opinion, exceptional. And while we are encouraged by the government’s decision to re-fund the equality rights component of the program, we emphasize that modernization may not require a complete re-vamping of the program. Instead, we suggest that the best aspects of the program, those that were effective particularly for people living in poverty wishing to claim their rights, be retained.

There were many unique aspects to the Court Challenges Program about which others have no doubt spoken. What is less talked about is the way in which the program served as an accountability mechanism to ensure Canada implemented international human rights obligations.

The United Nations has recognized the CCPC as a human rights mechanism relevant to our international human rights treaty obligations. For example, in the 1993 Concluding Observations from the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Committee stated that the program “enabled disadvantaged groups or individuals to take important test cases before the courts”. They commended the program and Canada for “[r]ecognizing the importance of effective legal remedies against violations of social, economic and cultural rights, and of remedying the conditions of social and economic disadvantage of the most vulnerable groups and individuals”.

In their Concluding Observations in 1993, 1998 and 2006 the Committee went further to recommend that claims at provincial and territorial levels be funded. We propose that this recommendation be implemented.

In our opinion, the review of the program also provides an excellent opportunity to consider taking steps to ensure that the program be both independent and protected by legislation.

In this regard, the CCPC should remain a free-standing institution – not associated with any academic institution – as it was prior to 2006. It should also retain its autonomous equality committee – made up of members from a variety of stakeholder sectors – to determine which cases would be supported by the program.

Historically, funding to this essential program has been cut many times – and this ‘here today, gone tomorrow’ approach must stop. Access to justice and rights claims for equality seeking group members should be accorded the highest protection from political whims. For this reason, we suggest that the program be enacted by legislature.

Ensuring the scope of the CCPC is relevant for people living in poverty

We encourage the Committee to assess the ambit of the program to ensure it can address the various types of equality rights claims that people living in poverty may wish to make.

Upon modernization of the CCPC, we recommend that the scope of the program be opened beyond claims made under section 15 of the Charter to include those claims under section 7, where claims focus on the right to life, security of the person and equality of people living in poverty and homelessness.

It is time for Canadian governments to acknowledge the close connection between the right to life and those who are the most marginalized – those who are living in poverty or who are homeless. For example, a study in Hamilton, Ontario found that those living in rich neighbourhoods had a 21-year longer life expectancy than those living in poor neighbourhoods. These numbers are not improving – in British Columbia, a recent study found a 70% increase in deaths among homeless populations in 2014 from the previous year.

As noted by Madam Justice L’Heureux-Dubé in the case R.v. Ewanchuck, sections 7 and 15 have special significance as they are the vehicles by which international human rights are implemented. In the context of the particular barriers faced by people living in poverty and the role of the CCPC in fulfilling human rights obligations – we encourage the Committee to seriously consider expanding the scope of the program to section 7 claims that might be particularly relevant for people who are living in poverty or experiencing homelessness.

This government has taken an important step forward as an international human rights leader in the re-funding of equality claims under the CCPC. Before us is an exceptional opportunity to ensure that those who are marginalized and stigmatized can access justice and claim their legal rights.

In summary, in their deliberations on the modernization of the program, we ask the Committee to: i/ retain the programs’ strengths from 2006; ii/ enact legislation; and iii/ extend the ambit of the program to include claims at provincial and territorial levels and to section 7 claims that interact with socio-economic inequality and discrimination.

This could be an important legacy offered by this government to the 4.9 million people living in poverty across Canada.

We look forward to answering your questions. Thank you.

Canada Without Poverty is a non-partisan, not-for-profit, charitable organization dedicated to the elimination of poverty in Canada. CWP is here because of your support. We would not be able to continue our work in eliminating poverty without your help. Please consider making a donation to CWP to support our work in ending poverty for everyone in Canada.