Canada is at a critical turning point for the 4.9 million people in this country who are living in poverty.

For years, civil society organizations like Canada Without Poverty (CWP) have been calling for a national anti-poverty plan, and now the Minister of Families, Children and Social Development, Jean-Yves Duclos has taken the first steps toward creating Canada’s first poverty strategy. To some it may seem that the path to an anti-poverty strategy is a long and overly-bureaucratic process – but the reality is that there is no panacea to poverty. When we look at the success of provinces and territories, it becomes clear that the road to poverty eradication is long-term and multi-faceted.

Every year CWP produces our signature publication: thirteen Poverty Progress Profiles. With the dismantling of the National Council of Welfare in 2012, Canada lost its primary mechanism for measuring poverty and social assistance in each province and territory, creating a major gap in vital information. Some organizations tried to fill this void; for example, the Caledon Institute’s Canada Social Report examines social assistance across all regions, but lost is the impact and insight of a funded council at arms-length from the government tasked both in-depth analysis of poverty in Canada as well as reporting to people in power.

The chasm left by the National Council of Welfare is even more problematic when one considers that Minister Dulcos has written that he will be “drawing on the expertise” of provinces and territories for the Canadian Poverty Reduction Strategy. This will prove challenging, as many provinces and territories are failing in their efforts to end poverty.

British Columbia is likely the province most cited as failing on ending poverty. In a review of our Poverty Progress Profile on BC, statistics illustrate the stark reality across the province. 1 in 5 children in the province live in poverty; this is coupled with the worst record of housing affordability in Canada. Despite all of this, BC does not have, and has never had, a provincial poverty reduction strategy.

Prince Edward Island is another example of a province where efforts have become static. Despite being host to high rates of food insecurity, unemployment, and low minimum wage, the province’s poverty strategy, which expired in 2015, has not been renewed.

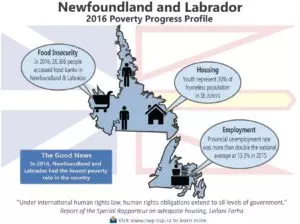

In contrast, there are a few examples of provinces and territories who have met with success. Newfoundland and Labrador, for example has gone from one of the highest rates of poverty among provinces and territories to the lowest rate. While this success has been attributed to initiatives such as indexed support payments and increases to minimum wage, it’s also the result of the province making poverty a high priority for all decisions made within the government as well as efforts to include people with lived experience in decision-making.

Québec was the first province or territory to create both a poverty reduction strategy and an Act to accompany the strategy. Importantly, Québec is also the province that has most overtly recognized that poverty is a violation of human rights by expressly citing international human rights instruments in both their first strategy in 2004 and most recent poverty strategy.

The Northwest Territories strategy has taken critical steps to ensure it does not become a stagnant document. It undergoes a review process with annual consultations with civil society – in particular with Indigenous governments – who provide feedback that informs an updated annual version of the plan.

Each of these elements in successful plans point to a holistic process more familiar in the international community, namely, a human rights-based approach to poverty. This framework requires particular steps, including:

- Making explicit reference to international human rights obligations;

- Ensuring human rights training for those involved in the strategy;

- Including those with lived experience of poverty in the development, monitoring, and implementation of the strategy;

- Developing measurable goals and timelines;

- Making the strategy a budget priority;

- Monitoring and reporting on the process and implementation of the strategy;

- Developing accountability and review mechanisms; and

- Providing claiming mechanisms to ensure rights holders have a place for their concerns to be heard.

The overall conclusion from our in-depth analysis of each poverty reduction strategy is this: for a poverty reduction strategy to be successful, it takes time, political momentum, dedicated resources and an understanding that governments must consider the lived realities of poverty in every single policy decision they make.

We can learn from those who have already been successful and follow the common threads of success, this means we need strong political will, a willingness to genuinely include those first voices of people living in poverty, and a firm commitment to re-think existing systems with the understanding that poverty is foremost a violation of human rights.

Michèle Biss the Legal Education and Outreach Coordinator at Canada Without Poverty.