In a country with the 11th highest Gross Domestic Product, it can be hard for some to understand the harsh reality that people in Canada are going hungry. But over the past few weeks it seems as though people across the country have been talking a lot about access to food.

Members of Parliament participated in the “Hunger on the Hill” awareness-raising event by fasting for a day. Last week, the Conference Board of Canada released their 2016 Food Report Cards on the ten provinces. The subject of food insecurity has even been a recent topic of discussion in provincial elections.

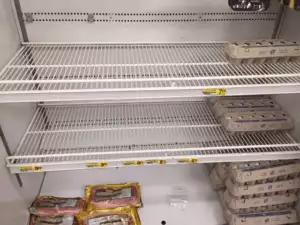

Canada Without Poverty (CWP) has been talking about food, too. With our recent visit to the North to host public conversations about human rights and poverty, we were able to see first-hand the exorbitant prices that lead to the highest rates of food insecurity in the country. In an Iqaluit store on a nearly empty shelf, cartons of eggs went for $7 a piece. Orange juice was $18. These high prices and supply problems mean that residents in Nunavut spend twice as much on food as the rest of the country on average. During the visit, CWP heard stories of hunger limiting participation at work or in classrooms – stories of children looking desperately for escape from constant hunger through substance abuse.

In fact, the problem is so prev alent that last week, a new report revealed that one-quarter of the territory’s population self-reported as moderately to severely food insecure, with just over half of Nunavut’s Inuit population at least occasionally going hungry.

alent that last week, a new report revealed that one-quarter of the territory’s population self-reported as moderately to severely food insecure, with just over half of Nunavut’s Inuit population at least occasionally going hungry.

While food insecurity is exacerbated in the North because of geographic isolation and high rates of intergenerational poverty influenced by trauma, discrimination and colonialism – it’s a problem that extends across Canada. 1 in 8 Canadian households across the country struggle to put food on the table, and food bank usage has increased in all provinces since 2008, except Newfoundland and Labrador.

There is increasing concern over food insecurity for university students as well. According to a recent survey, nearly 40% of students expressed some level of food insecurity – with 1 in 4 students saying food insecurity affected their physical health and 1 in 5 their mental health.

The Conference Board of Canada food report cards showed that nearly one in five Canadians surveyed said that they had gone hungry due to lack of food at least once in the preceding 12 months and, of the provinces, households in British Columbia and Ontario are more vulnerable to food emergencies.

Food insecurity is so rampant in Canada that it is now a country where some 850,000 people use food banks each month, despite the right to food being guaranteed by law. And food bank users aren’t just those experiencing temporary crisis or those already on social assistance programs– 62.2% of food bank users in 2014 were reliant on wages or salaries from employment. Food banks are vital to ensuring that those struggling financially and experiencing instability have access to food, but they aren’t a long-term or sustainable solution . As food bank usage soars in Canada, it is essential that we look towards comprehensive policy solutions to hunger and instability, rather than relying on stop-gap measures for a problem which impacts so many families and workers.

With 150 celebrations ramping up through the summer, much praise has been spoken about Canada as a global human rights leader, a distinction which sits in contradiction to the failure to meet many human rights obligations including access to food.

As a wealthy country with strong infrastructure, Canada has a host of options to address poverty as a whole, and food insecurity specifically. The Dignity for All model plan calls for a National Right to Food Policy built on collaboration with all levels of government (including Inuit Land Claim Organizations, First Nations, and Métis governments), food producers, community stakeholders, and food insecure people themselves. This must come alongside increased federal investment to address the very high levels of household food insecurity among First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, particularly in communities in Canada’s North. We have to listen to those affected by food insecurity, we have to be willing to change our current practices to effectively respond to those first voices.

Canada has a legal obligation, as well as a moral one, to allow people to feed themselves as part of living a dignified life, and it’s time our human rights leaderships extends to addressing hunger.

Laura Neidhart is the Development & Communications Coordinator for Canada Without Poverty.