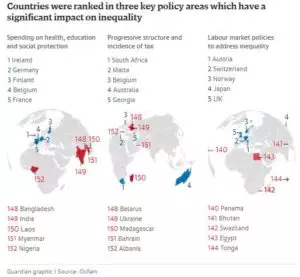

A newly-released report from Oxfam places Canada as 15th of 152 countries reviewed for their commitment to addressing income inequality.

The Index ranks governments across three policy areas: taxation, social spending on sectors such as health and welfare, and labour rights. While close to the top overall, Canada doesn’t have much to brag about overall. Canada ranks lower than many peer countries like the United Kingdom on social spending, and doesn’t crack the top five in any of the three policy areas.

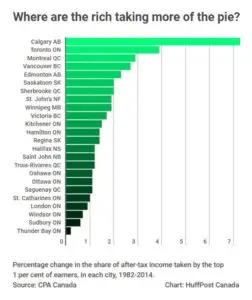

At the same time, data shows that the bulk of Canada’s inequality is  concentrated in urban centres – particularly Calgary, Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver – and that Canada’s income and wealth gaps are widening.

concentrated in urban centres – particularly Calgary, Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver – and that Canada’s income and wealth gaps are widening.

Poverty and inequality are closely interconnected. As Oxfam Canada has noted “[e]xtreme inequality is trapping millions of people in poverty because the same economic rules that allow extreme wealth also cause poverty…In fact, 700 million fewer people would have been living in poverty at the end of the last decade, if action had been taken to reduce the gap between rich and poor.”

When measured amongst poverty and inequality, there are a number of rankings where Canada does stand among its peers. For example, Canada stands at 12th out of 17 on income inequality in the late 2000s, 26th out of 35 for child inequality, and 37th out of 41 for child well-being. In light of these numbers, 15th out of over 150 may not see that bad, but the Oxfam report includes a much broader range of countries than those with a comparable Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and access to resources as Canada.

In comparison, Canada is an extremely wealthy country, with the 10th highest GDP in the world.

And while these international rankings can be helpful tools to contextualize the country’s global standing, they are only one piece of a larger system of how we’re fairing on our legal human rights obligations and government policies to take action to address inequality. For example, in noting our commitment to social spending in 2016, the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights stated that Canada was not dedicating enough resources to poverty and inequality as a maximum of its available resources.

Canada is also among m any countries that has committed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – international markers that replaced the well-known Millennium Development Goals – to reach objectives like a total eradication of poverty and hunger, and an overall reduction in inequality by 2030. These goals are in addition to the legal obligations Canada already has under the multiple international treaties it has ratified that oblige the government to fulfill rights like the right to food and adequate housing. So far, it’s not clear whether the government of Canada really takes the SDGs seriously; for example, it’s unclear whether Canada is developing a strategy to ensure that all laws, policies and programs are assessed under these SDGs to ensure that we are genuinely moving forward to meet these targets.

any countries that has committed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – international markers that replaced the well-known Millennium Development Goals – to reach objectives like a total eradication of poverty and hunger, and an overall reduction in inequality by 2030. These goals are in addition to the legal obligations Canada already has under the multiple international treaties it has ratified that oblige the government to fulfill rights like the right to food and adequate housing. So far, it’s not clear whether the government of Canada really takes the SDGs seriously; for example, it’s unclear whether Canada is developing a strategy to ensure that all laws, policies and programs are assessed under these SDGs to ensure that we are genuinely moving forward to meet these targets.

With the unveiling of Canada’s new feminist foreign policy and the recent celebration of the sesquicentennial, it is the right time for Canada to recommit to the objectives of our many obligations both on the international human rights level and implementation of the SDGs on the domestic level.

With national rights-based strategies, like a Canadian Poverty Reduction Strategy that includes the perspectives of those who have lived experience of poverty. It is only through the development of policies that use a foundation of human rights that we can hope to climb higher as international leaders, rather than falling behind on inequality.

Laura Neidhart is the Development and Communications Coordinator for Canada Without Poverty.