I am often asked, “Why human rights?”

And despite there being many good things that come out of the United Nations International Human Rights movement, it is the over-all covenantal agreement between state and the individual at the heart of it all that makes it work.

The agreement outlines not only the rights of every individual, which many think of when we say human rights, but also the obligations and responsibilities of the state and its respective subnational governments.

It is this obligation that came to mind for me last Tuesday afternoon when Ontario’s Minister of Children, Community and Social Services, Lisa MacLeod, announced the cancellation of the province’s Basic Income Pilot.

Since the pilot’s draft plan was presented to me early 2016, as a member of Ontario’s Income Security Reform working group, I have been a very cautious supporter of basic income. As someone who has lived a substantial amount of time in poverty due to disability, my concerns were of a pragmatic nature.

I needed to understand the unintended consequences of this method of income security: who it serves well and who it doesn’t. I needed assurances that if there was a significant change in income mid-year that the recipient had recourse to modify their monthly payment to supplement a loss in income. I needed to know that this system wouldn’t deter those with disabilities from attempting to earn income in a work trial or with chronic and episodic illnesses, due to fear they would live with less income the following year if the needed to stop working due to its annual reconciliation format.

Most importantly, I wanted to see how well individuals who needed non-monetary supports and services would fare in a pilot that disallowed them access to supplemental provincial services and programs.

And so the pilot began. 4000 households in this province are receiving Basic Income supports in 3 different cities (Thunder Bay, Lindsay, and Hamilton). Of the 1000 households in Hamilton participating in the pilot, one of those individuals receiving Basic Income is me.

I told very few people I had signed up. I enjoyed the anonymity of the program, the ability to say I was no longer on ODSP (Ontario Disability Support Program), escaping the stigma of being on supports. Despite working limited hours and my CPP-D payments, I still required transitional health benefits (drug, dental and vision care) even though I was no longer receiving ODSP income support. In entering the pilot, I was required to leave the ODSP program and benefits (consequently living with a less robust health package on BI), and to agree to not access provincial supports during the pilot. For anyone who has lived a significant amount of time on this system this is a scary proposition. Many of us fought a long time through adjudication just to receive ODSP benefits – and relinquishing this program brought for me triggering memories of when I first got ill and needed help.

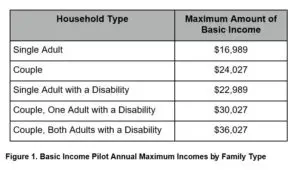

I do not receive the maximum amount possible due to my other income sources. In fact, 70% of recipients do not receive maximum amounts due to earned income. And for those that do receive the full amount, it is still only 75% of LIM-AT for Ontario – 25% below the relative poverty measure.

I’ll admit that I felt a bit embarrassed signing up for the pilot at first. With my CPP disability income and my part-time work, I was already doing significantly better than the $1151 that the ODSP recipients lived on, that I had lived on at one time. The amount I received was basically the “disability amount”, an amount generally used to realize the additional cost of living with illness and life-long limited employment income. Could approximately $500 a month mean that much to me? It could and did.

Within a few months even I noticed a change in how I felt, and more importantly in how I thought. Basic Income meant the difference between the stress of just getting by with no room for crisis and being able to weather unexpected expenses. December saw an unexpected $700 in home repair and mortgage renewal fees my credit union had forgotten to collect 6 months before. Without the pilot that would have meant going without food for at least week. The $500 a month also allowed me to begin to think of my future.

I began to wonder if I could finally get a degree part-time. I began to think of all the home repairs I have postponed and I could finally get done in my home. I began to plan how quickly and realistically I could eliminate the constant debt burden that builds-up living in poverty or on the edge of it. I started looking at assistive disability aids, assessments, and treatments not covered by the province. I began to think that within three years I could finally get ahead in ways that generally living with disability I would never be able to do.

And upon hearing the Minister’s announcement, all that came down in a resounding crash.

The impossible had happened. Despite reassurances during the recent provincial election, they had done the unthinkable. So many questions ran through my mind. How could they? What is the government’s obligation here? Is there a way to ethically end this pilot before the participants’ anticipated 3 years?

I have seen in my work the radical changes that have already taking place for those that had been mired in the Ontario Works system living on $721 a month. One who left a violent rooming house situation, settled, ate well, and voluntarily went for a mental health assessment. I saw many others who also moved to safer housing.

Can you ethically take away money when, on the government’s urging, people began settling their lives and anticipating the time to take a college program and begin a new life? In the midst of a massive housing crisis in Hamilton the same people will not be able to find housing at the same rate they had before the pilot, if any at all.

And for myself, I didn’t move, but I contracted for basic cable services. I know others signed up for internet and cell phones. Some have left employment to start school next month. Others have begun small businesses in anticipation of being financially assisted through the start-up’s first few years.

The impact on Lindsay, Ontario will probably be the most profound. As a saturation site, recipients of Basic Income form 10% of their population. How do communities thrive with that kind of loss?

The 2018/2019 Ontario Budget estimated $152.5 billion in revenues. The projected $50 million annually needed for this pilot is a mere 0.03% of Ontario’s projected revenues. The study itself is invaluable in studying the health and wellness impacts of approaching income adequacy.

Most importantly, how do you ethically remove hope? To take people from despair and indignity, raise their spirits and drive them back to hopelessness is a soul-destroying move. There have already been concerns of suicidal ideation, especially among those with mental health issues.

Under Canada’s international human rights obligations, the government of Ontario has an obligation to realize an adequate standard of living for all. In this case, they quite literally contracted with households to do so for 3 years.

It is important to remember these laws stand regardless of political winds, ideologies or populism. These laws form the basis of a covenantal agreement between myself and my provincial government. These critical human rights were formed to make sure governments could not and would not harm the people in their state. It is Ontario’s obligation as a signatory sub-government to make sure that does not happen.

Laura Cattari is the current President of the Board of Directors of Canada Without Poverty and the Campaign Co-ordinator at the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction.